Which intelligence?

"There are no questions about music on the test".

The Extremistans of intelligence

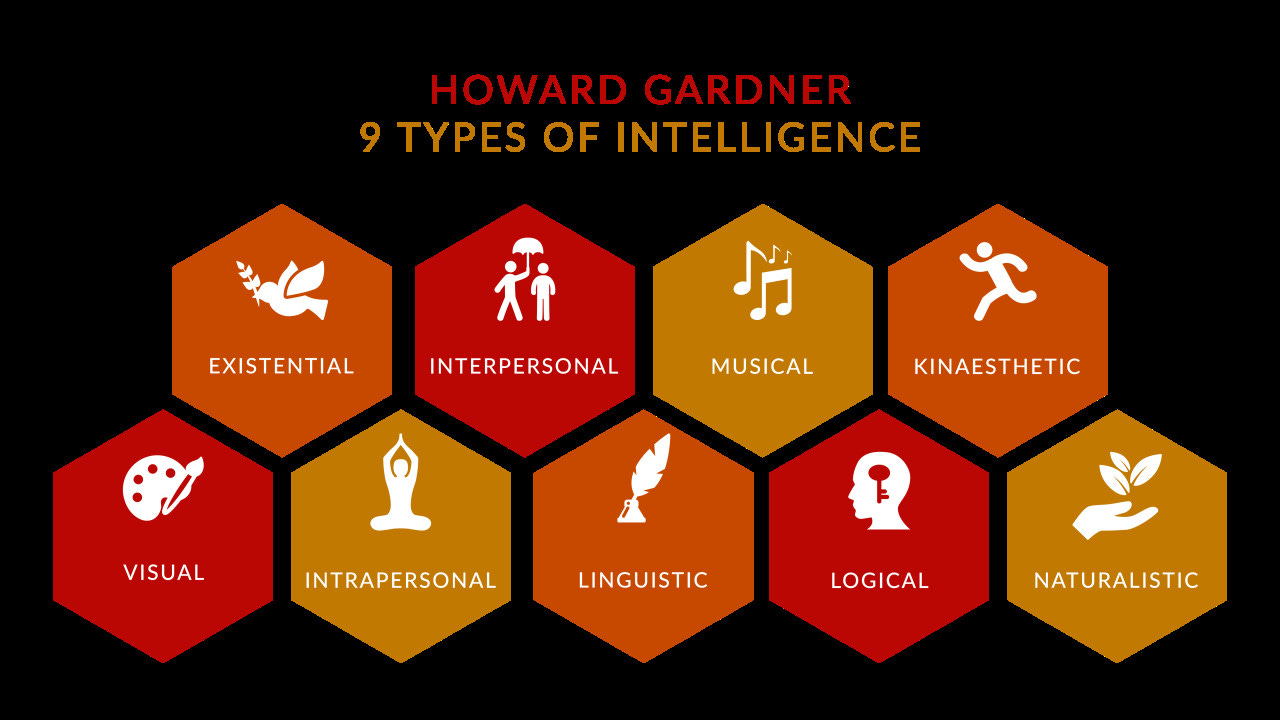

I caught up over the winter holidays with a movie I’d long planned to watch, Temple Grandin, the 2010 biopic where Claire Danes tackles the challenge of bringing her protagonist’s autistic mind to the screen. What the movie achieves - at least for the general viewer like me, who knows nothing much about animal behavior or animal science, and just the basics about autism - is to convey Dr. Grandin’s extraordinary empathy for large animals, and the way her mind seems to understand from the point of view of the animal what an experience is like, and how humans can and should make it better. So, I mulled over writing about how, in the Howard Gardner scheme of multiple intelligences, Temple Grandin would be atypically endowed with naturalistic intelligence, the way that Roger Federer exhibits kinaesthetic intelligence, I mean some people really live in their own Extremistan of intelligence!, and anyway how different some of these intelligences are from the ones that machines excel at (logical-mathematical, and now increasingly visual-spatial and linguistic-verbal), etc. - you’ve seen the framework before:

Then I thought: it’s a fairly contested theory, it has been critiqued for not having enough experimental evidence underpinning it, Gardner’s types of intelligence have ranged over time between eight and ten, and of course there must be some Silicon Valley types putting sensors on cows and claiming we can now do without the Temple Grandins of this world, etc. - so no, that was a false start and not enough to build a post on, nothing to see here, let’s move on and talk about something else.

But who knows what intelligence is? It would seem that consensus on the topic, to put it mildly, leaves something to be desired. Prof. Nello Cristianini, author of The Shortcut: Why Intelligent Machines Do Not Think Like Us, points out that his house cat, who is without a doubt intelligent, cannot make sense of the message Carl Sagan sent out on the Pioneer 10 and Pioneer 11 spacecrafts, and that the message was prepared for alien intelligences who most likely cannot either. What Sagan was looking for was not intelligence: it was another version of himself. (Anthropomorphism, anyone?) And Leonardo Da Vinci, who was a highly intelligent human, would not have fully understood the message. Even today, a lot of intelligent people are not overly concerned with the hydrogen atom or the periods of pulsars.

Moreover. As we pursue machines capable of Artificial General Intelligence, Benedict Evans said in his AI speech last month, we neglect to consider than “maybe people don’t have ‘general intelligence’ either” (exhibit: a list of common cognitive biases); jest aside, “we don’t have a theoretical model of what our intelligence is”. We don’t really know what it is, and whatever it is, we don’t know how to measure it. Google researcher François Chollet put a good amount of thinking into this, and came up in a 2019 paper with a formal definition that attempts to eschew the amorphous and stick to the maximum scientific rigor:

“The intelligence of a system is a measure of its skill-acquisition efficiency over a scope of tasks, with respect to priors, experience, and generalization difficulty”.

In this scheme, given two systems with a similar set of knowledge priors and a similar practice time with respect to a task that is not known in advance, the system that has been more efficient at turning its priors and experience into skills, i.e. has ended up with greater skills, is the more intelligent one. I am a bit puzzled by the emphasis on efficiency, which is definitely a thing in computer science (and should be, given the environmental costs of computation etc.), but when you attempt to translate it to the realm of human intelligence would be a bit like saying that both Heisenberg and Dirac were more intelligent than Einstein, because they published their breakthrough papers when they were 24, while Einstein had already been 26 when he published his 1905 papers, meaning that… Einstein was slightly less efficient? (I know, the fact of the publication of a paper is different from the “acquisition” of the skill needed for a milestone discovery in physics, but there aren’t a lot of other proxies we can observe, especially when the physicists involved are all dead.) Chollet seems not to have pursued his proposed measurement benchmark much further (the paper calls it Abstraction and Reasoning Corpus: “We argue that ARC can be used to measure a human-like form of general fluid intelligence and that it enables fair general intelligence comparisons between AI systems and humans”), but it didn’t seem to cover more than the usual machine-friendly types of intelligence in the - albeit dubious - Gardner framework, and what do I know, maybe Chollet will have a new paper out next week. Or someone else will. In the meantime, it seems to me that prizing efficiency above all in intelligence would be a bit like saying that synthetic diamonds are always superior to natural diamonds. Maybe the reason why most people prefer natural diamonds, impurities and all, is another cognitive bias.

Wikipedians, help needed

I invite you to consider the following: the English-language Wikipedia page for Human Intelligence is less than half as long as the page for Artificial Intelligence (90k bytes vs. 206k as of this writing); it is also available in 9 languages, while the page on AI is available in 147 languages. If Wikipedia is any indication, humanity seems to be severely underinvested in human intelligence. Probably as a result, the Wikipedia editors seem to have converged on a rather tortured definition of human intelligence, one that I assume no one is happy with. Here is the first sentence:

“Human intelligence is the intellectual capability of humans, which is marked by complex cognitive feats and high levels of motivation and self-awareness.”

I wouldn’t argue against the cognitive accomplishments (“feats”? why not “triumphs”?), but I do feel that motivation and self-awareness should be considered as rather different domains; otherwise we would not have had centuries of schoolteachers telling parents that their kid is “intelligent but lazy”, and there would be a requirement for anybody in search of higher self-awareness through meditation in a Buddhist monastery to pass some highly complex cognitive skills tests before being admitted, which the monks don’t require anywhere, as far as I know. But then, I am not a Wikipedia editor.

Fiction reading suggestions

If you’ve read me before, you know that I hardly ever write a post without a set of literary quotes for your perusal and enjoyment. This time, it’s not Borges. I was able at last to read Stella Maris, Cormac McCarthy’s last novel, published shortly before he died last year. McCarthy did not care for the company of other writers or artists, and preferred to spend his time with scientists. Late in life he was a trustee of the Santa Fe Institute, a network of researchers interested in complex systems. He is now, after shuffling off this mortal coil, an “Immortal Trustee” of the organization (I have no way to tell whether the other trustees have merely been inspired by the language nerds at the Académie Française or whether they are hinting at cryonics, well, whatever).

His Stella Maris protagonist, Alicia Western, is endowed with a remarkable degree of musical intelligence and an outstanding degree of mathematical intelligence: she has a history of spending eighteen hours a day doing maths and was close to Alexander Grothendieck before he more or less retired from the scientific world in his early 40s. Alicia is also a psychiatric patient, and a doomed one; whoever reads Stella Maris is likely to at least have heard that most of the events in the companion novel, The Passenger, take place after Alicia has committed suicide. In Stella Maris, which is presented as the transcript of a number of sessions with Alicia’s psychiatrist, we learn that she had been able to buy an Amati violin for three hundred thousand dollars (“It was the most beautiful thing I’d ever seen and I couldnt understand how such a thing could even be possible”), but she no longer plays it, because she could not be in the top ten violin players in the world. We also learn that she considers all psychometric tests “breathtakingly stupid and meaningless”, and the Stanford-Binet IQ test racist (which many would agree with today, while the novel is set in the early 1970s), because it does not, for example, measure musical intelligence:

There are no questions about music on the test. For instance. Apparently music doesnt count. So here's a black guy with a measured IQ of eighty-five who is by any metric you might care to choose a musical genius. Simply off the charts. But to the IQ folks he's little more than a halfwit.

Alicia tolerates her sessions with the psychiatrist, while mounting her challenge to the discipline:

Mental illness is an illness. What else to call it? But it’s an illness associated with an organ that might as well belong to Martians for all our understanding of it.

In spite of Alicia’s grief and despair, her intelligence sparkles throughout the dialogues. (Does suffering blunt our intelligence? does intelligence make suffering more likely? and what about suicide?) The novel never has a dull page. Here are a few more passages I underlined:

Doing math is a bit like selling door to door. You have to learn to handle rejection.

Mathematics is ultimately a faith-based initiative.

Women enjoy a different history of madness. […] We know that women were condemned as witches because they were mentally unstable but no one has considered the numbers—even few as they might be—of women who were stoned to death for being bright.

When this world which reason has created is carried off at last it will take reason with it. And it will be a long time coming back.

So, is it a sad book?

Are all your views so somber?

I dont consider them somber. I think they’re simply realistic.

Great piece. It’s nice to hear appreciations for Stella Maris. There are so many meaningful passages in there. Alicia is certainly intelligent (like I would know, hah) even with the debilitating hallucinations that haunt her.

Thanks Paola to rise a topic I was always discussing with my parents ( both engineers with top grades) while me and my brother were not.. I’m always fascinated by “intelligent people= analytical / logical ones “ thinking of me and the others like me “ less intelligent “ 😎😜. Ps paola you are in the first group eh !